Posted: 23 June 2023 | Last modified: 06 July 2023 | Expires: 19 March 2026

When it comes to head protection in HEMA, there hasn’t been a lot of innovation over the years. With most other HEMA gear, we’ve moved away from borrowing gear from other sports, and now use gear specifically made for the sport we play.1 For some reason, we’re still using three-weapon sports fencing masks, and then add some sort of supplemental back-of-head protection to fully enclose our noggins.

One outlier in the HEMA head-protection scene was Terry Tindall, who pioneered a custom-designed metal fencing mask that he sold under That Guy’s Products. Unlike most fencing masks out there, in addition to the metal exterior, the masks sport a suspension system, so don’t rely on padding for impact absorption. Among some early HEMA practitioners, the mask gained a following, and it still remains popular in certain clubs/schools. Tindall eventually sold the pattern after he decided he couldn’t produce the masks anymore, and so the masks have been sold by Edwin Gilbert at Horsebows since. Now starting at $450, they’re not inexpensive, so buying one naturally raises questions about how worth it they are.

When ordering, you have several options, to include ones that weren’t available when I ordered my mask (like ordering an admittedly safety-questionable visor). You can pick your leather trim/bib color, and a separate color for the inside of the bib. These colors are generally limited to whatever Gilbert has on hand at the time of production; inventory varies over time.

Masks come in either 16 gauge mild steel, or 18 gauge stainless. The mild steel versions are painted on the inside to help prevent rusting. The added benefit to this is visibility if you fence outside, as I found my stainless interior (which is unpainted) is horrible in the sunlight because of how bright it is. If you opt for the stainless (which I’d recommend), it may be worth painting the inside yourself if you do a lot of fencing in the sun.

While you have to send in sizing information, the masks are produced like a lot of other HEMA equipment, in that your sizing simply slots you into pre-sized templates. In other words, the masks aren’t bespoke, meaning the metal isn’t cut based specifically on your exact dimensions. Because of this, you don’t need to fret about getting your sizing exactly right; if it falls squarely into an existing template size, it should fit. Presumably, it’s only if you’re on the edge of two sizes that there may be concerns, but I don’t know if Gilbert follows up with customers when this is the case. I expressed some measuring inconsistencies when I ordered mine, which is when Gilbert brought up the sizing issue, and apparently my dimensions put me into a medium template.

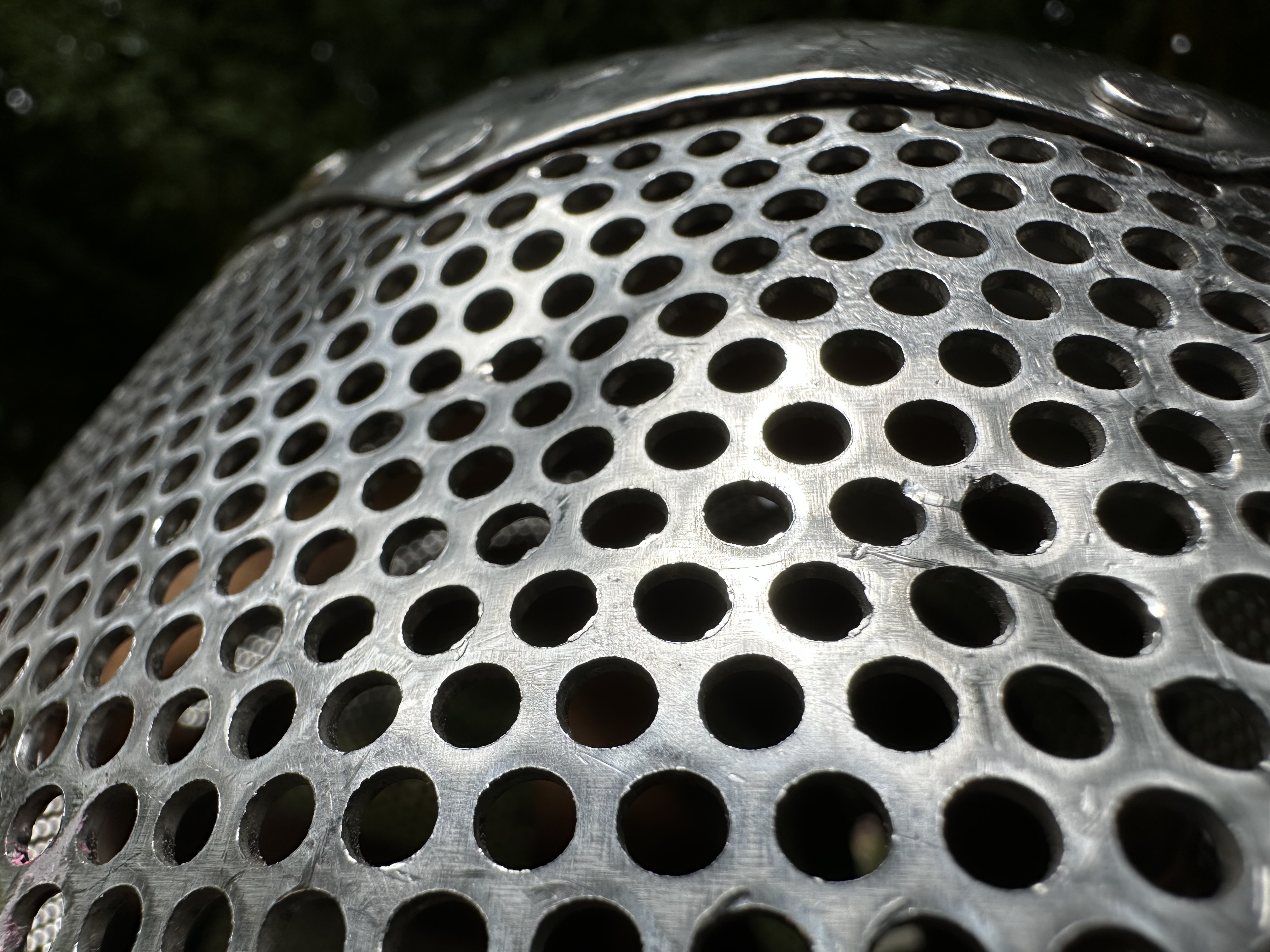

Gilbert also asked what form of HEMA I was doing; since the heaviest weapon I was using was longsword, he recommended a larger brow plate. If you primarily fight with lighter weapons, you can opt for a smaller brow plate and have more of the mask made of the perforated steel instead. One mask in our club, for example, is made entirely of perforated steel, and has no solid brow plate. Obviously, the more solid brow plate you have, the less visibility you have compared to a conventional fencing mask. Mine drops low enough at the center that I notice it, but it doesn’t get in the way of my fencing - it doesn’t obscure anything I need to see.

You can also opt for two chin shapes - a squared off design, or a more pointed design.

For the purpose of this review, my Horsebows mask is a stainless steel model with an “elaborate” suspension system and pointed chin. I received the mask in late 2018. The current configuration weighs 1,991g (~4.4 lbs).

With a regular fencing mask, your set up is mainly just confirming fit, and then maybe squeezing the mask exterior in order to dial the fit in a bit. Then you find an appropriate back-of-head protector/overlay, throw it on, and you’re good to go. Pretty much all fencing masks handle heat the same, with some overlays limiting heat dissipation. Generally, the padded overlays that wrap all the way around the mask tend to keep heat in, whereas bolt-on solutions for just the very back opening tend to mitigate heat better.

The Horsebows mask is more finicky upon initial set-up, but it’s cooler than regular fencing masks. The back-of-head protection on these is perforated steel, like the rest of the mask, and there’s no padding by default to stand in the way of heat getting out quickly. I say “by default” because you can add padding as a modification later, which some people apparently do, but it seems unnecessary for the most part. The suspension system is a leather set-up that needs some dialing in out-of-box. You can start by just fitting the suspension system to your head as-is with the basic buckles, but it’s quite possible you’ll have to grab a screwdriver and actually move which part of the suspension system is attached to the helmet via rivets; the suspension system has pre-punched holes to make moving it easy enough, but expect to spend about 45 minutes or so after receiving the mask to make it all fit just right for your head. If you’re anything like me, you’ll spend all this time, then go fence, and then tear the whole thing apart again to dial it in further. As the leather begins to stretch some in the following weeks, you’ll have to adjust the buckles a bit more, and may even want to punch new holes in the leather between the existing ones to dial in your fit in even better.

While the mask comes with some spare parts in case you lose a few rivets over time, there’s no locktite included with the kit, and that’s needed. I made the mistake of not locktiting all the rivets when I first dialed my mask in, and I quickly realized that the rivets will undo themselves just from the mask being hit over time. Once you have your suspension system dialed in, undo the rivets and locktite them, else you’ll encounter a failure eventually. I lost maybe three rivets over the years owning my mask, and while the first two didn’t cause a failure, the third caused the suspension system to separate from the mask. Fortunately, the suspension system didn’t come undone while I was sparring, but only after I was done. The mask was unusable at that point, and I needed to fix it to make the mask operable again. All three of these rivets weren’t locktited, so lesson learned.

The back-of-head protection swings open from the bottom, and there’s one leather strap coming off each side, connecting to one another at the front of the mask to keep the back-of-head protector closed. By default, these straps had a buckle connection on the front, which I found rather annoying to fasten and unfasten. Most of the folks I know who have a Tindall/Horsebows mask have modified this closure system, and I did the same. Initially I cut the buckles off and sewed in some neodynium magnets. This worked pretty well, but I found that matching polarities slowed the process of securing the mask. I eventually removed the magnetic closure and just added snap-on buttons. My original intention was to find an enclosure system I could use with gloves, and the snap button system worked best with light gloves. If you’re wearing heavy gloves, forget about finding an enclosure system you can operate, and just get used to taking your gloves off before messing with your mask.

The only other mod I made was adding a thin sheet of self-adhesive EVA foam to the chin area of my mask. Because the mask is secured at the top of the head, thrusts to the lower chin area tend to allow the mask to swing, and this occasionally causes waffling to the side of my chin impacted by the thrust. I suspect that because I ordered the pointed chin version (vs the squared chin), the angle at which my mask’s side walls come down is steeper, offering a bit less room between my chin and the mask walls. That said, even folks I know with Horsebows “square” chin masks have this issue, but maybe not as commonly as I do. The impact, depending on severity, either leaves a small mark where the perforations are, or the perforations cut into my skin and tear it up, leaving me with a slightly bloody chin. To mitigate this, the foam I added offers a tiny bit of padding, and prevents the metal of the mask from cutting into my skin. I didn’t take the EVA foam very high, and I may have to raise it a bit more, but I feel the foam addresses the brunt of the issue (which is less the impact of the sidewall, and more the gauging the perforated steel does to my skin after the impact).

Another thing I’ve considered of late is to scrap the EVA entirely and get much thicker pads that “anchor” my chin in place, much like with a conventional fencing mask. This should completely solve the issue of my chin getting smacked after a hard thrust to the bottom of my mask, but it would also work against the “pendulum effect” of the suspension system, which mitigates most minor hits (i.e. the mask “swings” instead of transferring all force to my neck and head). I plan to play with this in the future and will update this article accordingly when I do.

Until about a week before this article was published, I used my Horsebows mask exclusively since I got it, for both HEMA and eskrima. I never felt my head wasn’t protected, or that the exterior of the mask was unsafe. I know there are folks out there who are adamant that they don’t trust anything not made by a big commercial company for getting hit with swords, but it’s worth noting that fencing mask producers test their gear for Modern Olympic Fencing, not HEMA, so whether a mask holds up against bigger swords is anecdotal either way - the regular mask crowd just has more anecdotal data. That said, the Tindall mask design has been in use for over a decade, has been used in intense competitions, and has a track record of preventing injury. Whether that prevention is “better” than regular fencing masks is what’s up for discussion.

There’s a whole rabbit hole we can go down discussing how HEMA masks prevent concussions, and there’s a lot of science behind the topic. The big take-away is that masks should aim to do two things: stop the kinetic impact of a sword causing damage to your head, and prevent brain trauma. To be clear, the former point addresses superficial damage, like bruising, cuts, etc. to the exterior of your head. The latter, of course, addresses either concussive forces, or less-than-concussive forces that might also lead to long-term issues (e.g. brain trauma).

To address the former type of injury, traditional fencing masks seem to work just as well as the Horsebows mask. That is to say, most folks don’t complain of head bruising or cuts after being struck with a sword, the aforementioned mask waffling not withstanding. In other words, all fencing masks used in HEMA are pretty good about keeping the sword blade on the outside of the mask and away from your head. So generally speaking, unless there’s horribly inadequate padding in a conventional mask, no physical injuries like bruising should ever happen, and I think HEMA practice over the years bears this out pretty well.

The main argument for suspension systems here is that because the mask walls don’t sit against your head, most impacts don’t result in the mask colliding with your head, or rely on any padding contracting to absorb a hit. Instead, lighter hits are lessened by the mask “swinging” or otherwise shifting on your head, instead of the force of the hit being transmitted directly to your head through the padding.

The issue of concussions is more complicated, and from the research I’ve done, it doesn’t appear that a suspension system has any real benefit over padding, as it seems neither is sufficient to mitigate concussion-level forces. Either the padding itself has limits in how far it can contract before the rest of the impact is transmitted to your head, or the limits of a swinging suspension system will be reached similarly. Ultimately, your neck remains a weak link, and no amount of padding, weight, or fancy suspension system will mitigate enough force to reduce a hit with real concussive force to a “safe” level. The best things HEMA practitioners can do to prevent concussions is to use lighter and more flexible blades when fencing with intensity (i.e. feders vs blunts), and to prevent as much “stickiness” between blades and masks as possible. That means not using rubber tips (tape them if you do), and to use masks that allow blades to glance off them as much as possible. A third, non-equipment-related practice would be to strengthen the neck, which takes time.

Regarding stickiness, the Horsebows mask does a pretty good job; the exterior is smooth enough, and because there’s no padding overlay made of a comparatively “sticky” textile, hits are more likely to glance off than if they hit a padded overlay.

That leaves us with the issue of subconcussive impacts, which can still lead to chronic traumatic encephalopathy (CTE). Unfortunately, we don’t actually know how hard hits need to be to have a cumulative effect that may lead to CTE. Are we talking forces that are 75% of concussive levels, or more like 25%? Is it even lower? All we know is that subconcussive impacts, which do not result in symptoms (unlike a concussion) can still lead to CTE, so we want to mitigate them as best as possible. Since there are so few answers here at the moment, however, it’s impossible to say whether the suspension system in the Horsebows mask actually makes a difference.

I haven’t taken a hit in the Horsebows mask that I felt was unnerving or painful other than the few times the mask waffled my chin. Cuts to the front, sides, and top of my mask were fine, as were thrusts to any area other than my chin. The suspension system also comes with a thin leather chin strap - most folks I know removed this, but I kept mine in. That strap makes putting the mask on and taking it off a tad more difficult, but it gives me a little piece of mind. I never felt I took a hit that required the strap, but arguably if you end up on the ground or something odd happens where your mask could get popped up, the idea of the chin strap as insurance makes some sense.

There are two kinds of rivets on this mask: the Chicago screws that require locktiting (mentioned above) which hold the suspension system to the mask, and the basic, smaller rivets that hold the individual metal sections to one another and the bib. Those same rivets are on the bib itself to provide better cut and thrust resistance. The smaller rivets not on the bib can sheer over time; I’ve lost two of them to date, but they were easy enough to replace. There were enough in my spares kit that I haven’t had to purchase any more yet, but eventually I’ll have to buy a few more to have on hand. Obviously, this isn’t just an age thing but an intensity thing; take enough hard hits to those rivets, and they’ll eventually break.

I’ve had no issues with the bib; it functionals well and has held up fine. One of the rivets I had to replace held the very end of the bib to the mask on one side, but the leather wasn’t damaged. I should note here that unlike conventional fencing masks, the bib on the Horsebows mask is not Newton-rated, which may play into the few events that disallow these masks.

The leather trim of the mask will obviously need to be replaced eventually. Mine has held up well, but there’s one tear on one side of the mask that will need to be addressed eventually, either with some glue for now, or with a complete trim replacement in the distant future if similar damage happens elsewhere. The trim leather is rather thin, so if I eventually do a complete trim replacement, I may opt for some thicker leather here, but of course that will add a little more weight to the mask, and may require bigger rivets to secure properly. (That said, one of my instructors has a mask over a decade old, and the trim is still going strong.) The trim covers the edges of the perforated steel sheets, which I imagine aren’t rounded, so while it serves an aesthetic purpose, is also prevents getting scratched by what are presumably unfinished edges underneath.

There are observable dings and dents on the mask face from thrusts and cuts, but nothing significant. You can find reports online about the front “failing” over time, but there’s only one real report I was able to track to a documented event at SoCal Swordfight, in which a horizontal cut from a heavy saber folded one side of the mask in.

)

)

The mask wearer was not hurt, so arguably the mask did its job, but how structurally compromised the mask was from thereon out, I don’t know for sure. (Presumably, the mask face could be hammered back.) A couple engineering friends gave me similar answers to this question, suggesting a structural decline of maybe 5-10% after the front is hammered back. That sounds bad, but remember that this seems an outlier, and that there don’t seem to be documented reports of similar incidents out there. And, of course, conventional masks can have similar issues with mesh caving in over time, or separating from the mask. (I also don’t know if the individual at SoCal had a mild steel or stainless steel mask.)

The non-perforated brow plate of my mask seems in great condition, and I have no concerns about the structural integrity of any section of the mask now, or moving forward.

A common anecdote about these masks is that quality control dropped substantially after Tindall sold the pattern to Gilbert, yet the people who seem to repeat this rumor don’t seem to know a ton about the masks, and haven’t handled many of them. We have about seven or eight of these at my one club, including at least one Tindall original, with the latest Horsebows mask purchased only a couple years ago. Having heard these statements time and time again online, I inspected our club’s masks in an effort to bring some facts to bare. Obviously this is a small sample size compared to all the masks like this out there, but it does cover examples within a decade of production, spaced out pretty well.

In my review, I didn’t see any quality differences across masks. The parts Gilbert uses appear to be the same ones Tindall used, with at least one mask in our group having different rivets, but Gilbert appeared to go back to the original rivets in later productions.

Two folks from my club indicated there were quality issues with their suspension systems. One individual felt the leather in the suspension system was badly cut, ripped the whole thing out, and redid his from scratch using new leather he bought. The other individual felt he couldn’t dial the suspension system in well enough, and even tried moving where the suspension system was attached to the mask, and eventually just abandoned it.

At least two owners indicated they felt the edges of the metal plates, where they overlap, weren’t properly filed/rounded (leaving sharp corners), and so took a file to the edges themselves to round them off. I never saw these masks in their original state, though, so can’t comment myself on how bad this was; by the time I looked the masks over, the finish was identical to the masks that didn’t have these issues.

Worth noting is that the two masks with suspension/fit issues were also the same ones that apparently had issues with the sharp steel edges.

Masks produced both before and after the masks with these issues seemed to ship without problems, so either the problems in fit and finish were during one period and were worked out, or they appear intermittently in production.

I recall when ordering my mask, Gilbert indicated he had some folks helping him put the masks together, and that he found it hard to keep good workers around. My speculation is that any finishing problems on these masks may have been from the folks helping Gilbert, and not something that’s inherent in Gilbert’s process. In any case, even the masks with “rough edges” or with non-ideal suspension systems didn’t have functional problems, or any issues with structural integrity or safety.

Looking at all the masks side by side, I don’t think anyone could pick out the Tindall original. The patterns really do look identical, with rivets in the same spots, and only variations in some of the suspension systems notable. Based on my review, I wouldn’t hesitate to order a Horsebows mask if outside comments about quality control have you second-guessing.

I’m quite happy with my Horsebows mask, and from a purely subjective perspective, feel that this is what a proper HEMA mask should look like. But, is it worth the extra price?

At the end of the day, I’m not convinced the Horsebows mask has a lot of leg up on masks like the Wukusi Cobra, at least as far as safety is concerned. The suspension system is a primary selling point, which I intuitively feel is better than padding for concussion mitigation, but the facts seem to suggest my intuition is wrong here; even if you account for added padding, the suspension system is unlikely to prevent a concussion from real concussive levels of impact (e.g. a hard thrust from an unforgiving sword, at speed, with bodyweight behind it). Research is still ongoing about the effects of subconcussive impacts, so right now, there’s insufficient data about whether the Horsebows’ suspension system mitigates these kinds of impacts better than a conventional mask.

From a heat management perspective, the Horsebows mask is great. You don’t have padding up against your head, so airflow is better, and long-term you won’t have to deal with a stinky mask.

If aesthetics matter to you and you like the look of the Horsebows mask, I wouldn’t hesitate to recommend it. It’s a fantastic mask that feels substantial, and it’s unlikely you’ll encounter a tournament in North America that expressly forbids it.

One of the reasons I bought the mask in the first place is I wanted something that would last my entire HEMA career, and that didn’t require washing any padding. If you work out the numbers, however, for the cost of this mask, you can buy two to four conventional masks over the years, depending on how fancy you want to go. So that’s certainly something to consider if you’re looking at the economics of this purchase.

Knee and shin protection are still exceptions, though there are still HEMA-specific models available. ↩